GPT and Technofetishistic Egotism

AI is having a moment! New models like ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion have captured the imagination and challenged assumptions about the capabilities and limits of machine learning. But how do these “generative” models work? What does a future where these models are commonplace look like? And what are their limitations? I’ll focus primarily on GPT, but some of this analysis will also apply to image generation models like Stable Diffusion as well (and indeed, with GPT-4’s new visual capabilities, the line between these two categories of models is now rather blurry).

Terminology

Let’s quickly review some jargon:

-

A generative model is a type of machine learning model that produces outputs (text, images) based on a prompt (usually text, but also sometimes an image). This approach contrasts with “supervised” learning in that, rather than trying to predict a specific target (label, number, etc), the model is used to generate novel outputs. (Note that this is a difference in usage, but—as we will see—not necessarily a difference in implementation.)

-

A large language model (LLM) is a deep learning model (i.e. built using neural nets) trained to predict conditional token probabilities. In layman’s terms, these are models that are given some words (like the start of a sentence) and predict which words are most likely to come next. These are called “language models” because, in order to do this task effectively, the model must have some approximate representation of the syntactic structure of the language used for the inputs. (They are “large” language models because they’re enormous, even for deep learning—65 billion parameters for Facebook’s LLaMA)

-

GPT (“general purpose transformer”) is a specific class of large language model constructed by OpenAI, and ChatGPT is a chatbot interface to GPT. There are various versions of GPT, most recently GPT-4, although ChatGPT (as of this writing) is built on GPT-3.5. It is important to note that, in spite of the name, OpenAI does not publish or make publicly available their model weights, and OpenAI is a for-profit business whose primary source of revenue is API-based access to their models. (More on this later.)

The release of GPT and similar generative models can be viewed as progress toward “foundation models” (and this appears to be OpenAI’s preferred framing of GPT). A “foundation model” is a general-purpose model that can be adapted to a wide variety of tasks with minimal fine-tuning required. ChatGPT is an example of this approach: the underlying model (GPT-3.5) is provided with an initial context (instructing it to behave like a helpful chatbot, don’t output profanity, etc) and then user inputs are appended to the end of this context. The resulting string (context + prompt) is passed through the underlying LLM to produce the output returned to the user.

The interesting thing about this process is that no re-training of the model (re-training meaning adjusting the model’s parameters) is required, instead adaption for different tasks can be done at runtime by supplying different contexts. This is very appealing for companies like OpenAI because actual re-training to customer use cases is computationally expensive, requires complicated multitenancy to manage per-customer or per-use-case model instances, and potentially requires sharing model weights with customers. (And the model weights are the secret sauce here; there is no other technical moat.)

Unfortunately, large language models are unlikely to be the general-purpose foundation model OpenAI seeks.

To explain why, let’s look at how these models work.

Statistical language models

A language model is a probability distribution over token sequences. Large language models are part of a broader family of statistical language models. As the name suggests, these models look at statistical properties of text to identify conditional probabilities. Mathematically, these models are functions

\[f_{k}(x_{1},\ldots,x_{n-1}):=P(x_{n}=w_{k}|\underbrace{x_{1},x_{2},\ldots,x_{n-1}}_{context})\]where the set \(\{ w_{1},w_{2},\ldots,w_{k},\ldots\}\) is the vocabulary of the model and $f_k$ is a function returning the probability of vocabulary token $w_k$ appearing given the context.

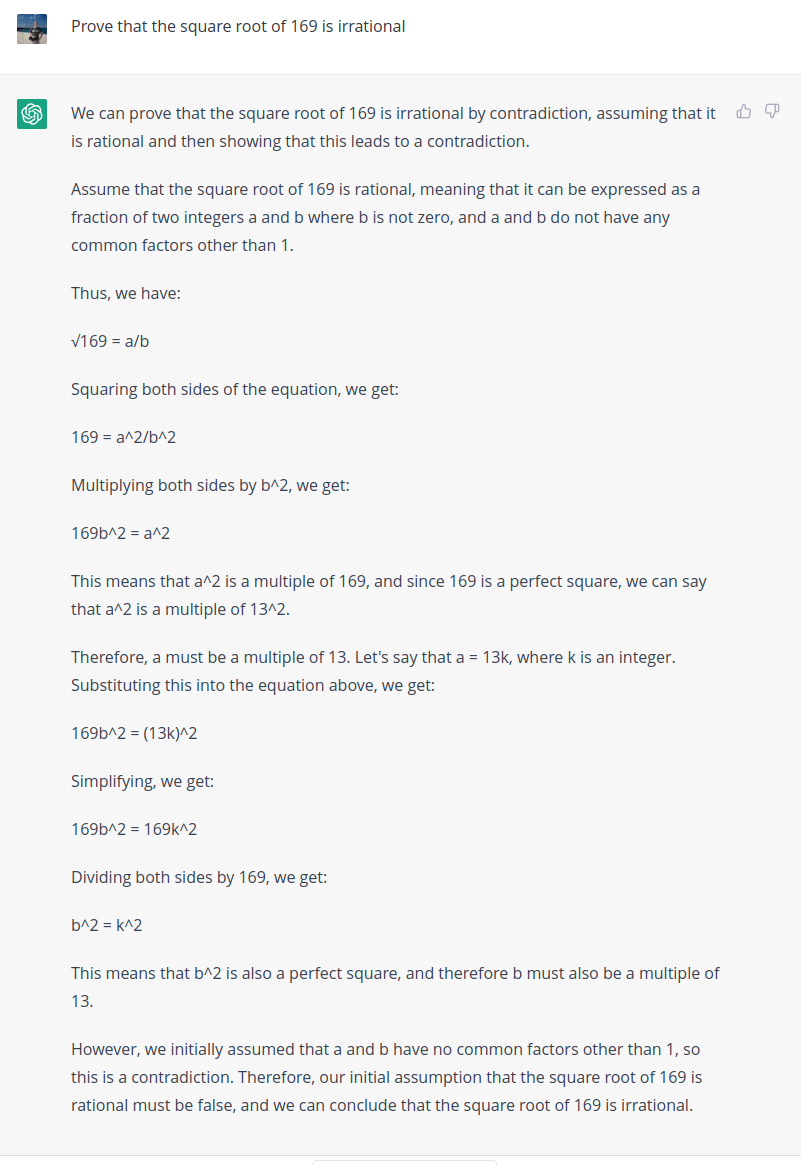

Predicting the next token given a sequence of preceding ones is called text completion. An example of how to use a language model on this task is below:

Here, we are trying to predict which token (word) comes next given the preceding tokens (the “context”):

"The", "quick", "brown", "fox", "jumps", "over", "the", "lazy"

The model in this example assigns probabilities of 0.94 to the token dog, 0.05 to log, 0.01 to banana, and 0 to every other vocabulary token.

This model determines that the presence of brown in the context increases the probability of dog by 0.25 units, fox by 0.5 units, etc.

(In a typical model all of the tokens in the context would impact the resulting probability, and potentially in a nonlinear way; for simplicity only three are illustrated here.)

The simplest version of such a model (a Markov chain) can be implemented in just a few lines of Python:

from typing import List, Dict, Tuple

import numpy as np

from numpy.random import default_rng

class MarkovLM:

def __init__(self,

vocab: List[str],

probs: Dict[Tuple[str], np.ndarray],

window: int = 2):

self.window = window

self.vocab = vocab

self.probs = probs

self._rng = default_rng()

@classmethod

def fit(cls, corpus, window: int = 2, temp: float = 1.0):

vocab = set([y for x in corpus for y in x])

# <SOS> = "start of sentence", "<EOS>" = end of sentence

vocab = ["<SOS>", "<EOS>"] + sorted(list(vocab))

vocab_lookup = {x: i for i, x in enumerate(vocab)}

probs = {}

for sentence in corpus:

# pad the sentence with "start of sentence"

# and "end of sentence" tokens

s = ["<SOS>" for _ in range(0, window)] + \

sentence + ["<EOS>"]

for i in range(window, len(s)):

x = s[i]

context = s[i - window:i]

context = tuple(context)

if context not in probs:

probs[context] = np.zeros(len(vocab))

probs[context][vocab_lookup[x]] += 1

for k, v in probs.items():

probs[k] = v / v.sum()

return cls(vocab=vocab, probs=probs, window=window)

def predict(self, context: List[str]) -> str:

context = ["<SOS>"

for _ in range(0, self.window - len(context))] + \

context[-self.window:]

x = tuple(context)

probs = self.probs[x]

return self._rng.choice(self.vocab, p=probs)

This is model is called a Markov chain because it satisfies the Markov property: it assumes that the probability of each subsequent token only depends on the previously observed context.

The window parameter controls the “n-gram” size of the model, that is, the number of tokens used to predict the next token.

There are a few fairly obvious deficiencies with Markov models, particularly as implemented here:

-

If a particular sequence of words does not appear in the training data, it cannot be generated by this model. This is because the corresponding token probability (determined by word frequencies) is 0. We can mitigate this particular issue by introducing a “temperature” parameter (by analogy with statistical mechanics) to interpolate between “all possibilities are equally likely” and “only return the most probable class”. However, in doing so, we’ll rapidly hit the next problem:

-

If a particular context was not seen in the training set, the model will not be able to generate any predictions. This problem is called “sparsity”. To fix this we need to come up with a scheme for how to estimate probabilities for novel contexts.

In a sense, this last deficiency is the whole game: for a vocabulary with just $100$ tokens in it and a two-token context, there are $100^2$ possible contexts in this Markov approach. For long contexts—and GPT-4’s context is up to 8,192 tokens—it rapidly becomes infeasible to construct a corpus that covers more than a negligible fraction of every possible context. One can imagine a number of hacks to tackle this challenge: perhaps we could embed some additional information into the model (such as the language’s grammar, say) or tag our tokens with their part of speech (to constrain the space of possible contexts). It would be better, however, if support for unseen contexts was built into the model itself. This is the idea behind neural network-based language models (which include LLMs).

The main innovation of LLMs is their ability to accurately interpolate token completion probabilities for novel contexts. The way they accomplish this is by treating it as a continuous space modeling problem, rather than a discrete one: tokens are represented as vectors in some latent space \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\), and these vectors (called “word embeddings”) are mapped back to words by looking for the closest known token vector from the model’s vocabulary.

I’ve written before about LLMs (here and here), and better writers than I have discussed the specific transformer architecture used in models like GPT and LLaMA, so we’ll skip the technical details here. To summarize, the transformer is a genuine advance in deep learning, and this approach is stupendously good at text completion.

But are these LLMs suitable foundation models? Well, in a word, no.

GPT’s foundational shortcomings

To see why LLMs like GPT are not truly general-purpose models (and, I will argue, not even on the path toward them), let’s highlight a few important features of these language models.

Language models are only accidentally correct

Take a look at the conditional probability expression from the previous section:

\[f_{k}(x_{1},\ldots,x_{n-1}):=P(x_{n}=w_{k}|\underbrace{x_{1},x_{2},\ldots,x_{n-1}}_{context})\]The subsequent token probability depends only on the previous context, and in statistical language models (which LLMs are undeniably an example of), the token probabilities are computed based on statistical properties of the text. There is no step in either the training or inference processes that ensures that the output that the model produces in response to a query is “correct” (for an open-ended query, what would that even mean?), and, even if there was, “correctness” would have to be derived from the corpus somehow (or introduced through an infeasible text labelling exercise).

In other words, the output of an LLM will only be at most as “correct” or “true” as its training data is in aggregate. And, moreover, correctness is not part of the optimization criterion, only token probability is. Consequently, at risk of anthropomorphizing the model, whether an LLM’s output is correct or not is entirely inconsequential to the model itself.

In a triumph of marketing spin, OpenAI has managed to brand factual inaccuracies in LLM’s outputs as “hallucinations”, but make no mistake—from the model’s perspective there is no difference between hallucinations and “correct” outputs. Instead the model should be better understood as perpetually hallucinating, and occasionally those hallucinations just happen to be accidentally correct.

A corollary of this is that the LLM will be confidently incorrect, sometimes to an extent that resembles gaslighting.

Attempts can be made (such as reinforcement learning from human feedback) to apply a “correctional” auxiliary process on top of the LLM, but these should be understood as a kind of output weighting scheme. In particular, they do not change the fundamental mechanism by which the model generates its outputs.

Language models do not “understand” language

At first blush, this claim may seem somewhat more controversial than the previous one. How can an LLM generate readable, intelligible text from a novel prompt if the model does not encode some kind of understanding of the language?

In fact there is a (hypothesized, but broadly accepted) correspondence between statistical properties of words and their semantic content. This is called the distributional hypothesis, and it asserts that words which appear in similar contexts (i.e. have similar statistical properties) have similar meanings (semantic content). An intuition for this is: suppose you have never heard the word “exam” before, but you see that it can be used interchangeably with the words “test” and “assessment.” Then you may reasonably (and correctly) conclude that “exam”, “test”, and “assessment” are semantically similar, that is, they mean the same thing.

Crucially, this observation doesn’t tell you what “test” actually means, but it does allow you to fake it: if someone asks you what “test” means, you could correctly respond that it means “exam” (without knowing what “exam” means). If you’re clever, you may even broaden your list of “test”-similar things to include multi-word phrases (“thesis defense” or “scored, timed school assignment”).

And this is precisely what LLMs do! If you have a perfect statistical model of the language, you can quantify exactly how similar or distinct particular a particular token’s usage is, and you can construct a web of relationships between them.

However, this web is cyclic and self-referential: there is no connection to anything outside of the tokens, and you could equivalently build such a model on a corpus constructed from an arbitrary and random collection of meaningless tokens. There is no point in this process where semantics are injected into the model.

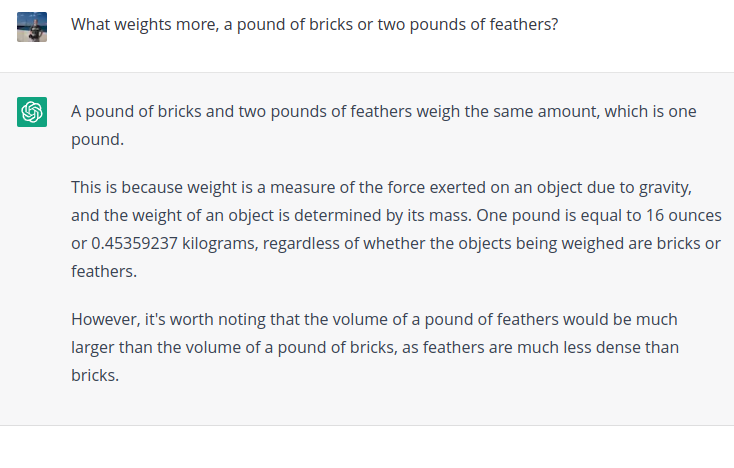

Observe an example of this in the following exchange: I ask ChatGPT which weighs more, a pound of bricks or two pounds of feathers?

ChatGPT readily asserts that “a pound of bricks and two pounds of feathers weigh the same amount, which is one pound”, despite the obvious logical error. This is because, in place of any understanding of the text, an LLM only possesses statistical associations.

I’ve made some strong claims about the shortcomings of LLMs, so included at the end of this post is an appendix demonstrating additional failures of exactly the types described above.

Technofetishistic Egotism

If GPT isn’t capable of reasoning or understanding, why do people think it is? Why is everyone so worked up about this stuff? How did we get to this point? What does it all mean?

There are a few different angles to unpack here.

If ChatGPT can’t think, why do people believe it can?

The short answer to this question is that chatbots like ChatGPT provide a very convincing imitation of a human conversationalist and that humans are easy to trick. Even some of the software engineers who work with these models believe they are capable of cognition. But why is the illusion so convincing? I think there are a few factors here:

-

The anthropomorphic impulse: Humans are wired to anthropomorphize. Humans are empathic creatures. We imagine complex internal emotional states for our pets, we see the hand of fate in random occurrences, and we even sometimes ascribe intent to inanimate objects. Every data scientist reviewing model outputs with a nontechnical audience will be familiar with this phenomenon. When an output is incorrect, people jump to volunteer an explanation: “oh, the model must have thought …” But the model didn’t think anything: the computer multiplied some numbers together, maybe did some addition, and then returned the result of that calculation. “Matt,” you might object, “how do you know that human cognition isn’t just a bunch of math?” But the burden of proof does not rest with the skeptic—and I have yet to see a proof that cognition can arise from a mathematical expression.

-

If a human needs cognition to perform a task, we assume that anything performing that task also utilizes cognition. This is a related, but subtly distinct factor to the previous one. Here is an analogy: Imagine a simple program that accepted two non-negative integers, each less than 100, and returned their sum. Under the hood, the program could be actually adding the numbers, or it could just contain a lookup table with every possible combination of inputs. If you looked only at the inputs and outputs, you would likely assume that the program was doing addition—that is how a human would do it. Similarly, looking only at an LLM’s inputs and outputs, it is easy to assume that it is doing something similar to what a human would do (and, because of the nature of the model, it is actually extremely difficult to interpret what is actually happening under the hood.)

-

Companies, especially OpenAI, want people to believe LLMs are the path to general-purpose artificial intelligence. OpenAI is a for-profit business, and they are in the business of selling access to their model. This infects every public-facing statement they make—even OpenAI’s research papers should be best understood as marketing material for their product. Moreover, building these models is obscenely expensive: if GPT is fundamentally a glorified auto-complete tool, then the return on that investment has a much lower ceiling than it does if GPT just needs a few more iterations to become a universal foundation model. Indeed, because of the huge expenditure required to build these models, tech companies selling “AI-powered” products are essentially the only source of LLMs.

-

Finally, LLMs are optimized to appear human. This is literally baked into the optimization criterion: an LLM is trained to identify which text is most likely to follow after its input. The text used for training is written by humans, and written for humans. An LLM exhibits quirks, expresses emotions, or makes common typos in its outputs precisely because it is just mimicking the human authors of its training corpus. It is persuasive and compelling because the human authors wanted their work to persuade and appeal to its human readers.

The Hubris of Artificial Intelligence

Given that LLMs really don’t work all that well at tasks requiring logical deduction or reasoning, why is it that their creators continue to promote their use in other fields?

One possibility is that they know the tool is currently insufficient for the task, but they want to make the sale (and perhaps they genuinely believe that it’s just a matter of scale before LLMs actually do get there). I think this is either deeply cynical, or at a minimum misguided. The notion that scale (meaning bigger models and more data) will lead to qualitatively different behavior from these models—and true deductive reasoning is a qualitatively different behavior—is not supported by the evidence we have today. GPT-4 makes the same classes of errors as GPT-3 and GPT-2 did before it, and can be “tricked” in the same ways. Suggesting that scale will solve the problem is akin to claiming that climbing a tree gets us closer to the moon, so we just need to find bigger trees: not every destination has an iterative path to it.

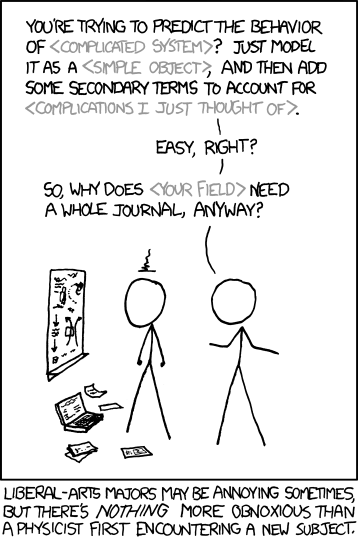

A second possibility is that the creators of these models believe that “non-STEM” subjects do not actually require a comparable level of cognitive sophistication and reasoning ability. This attitude is unfortunately commonplace enough to get lampooned in shows like Big Bang Theory, as well as by XKCD:

Borrowing a turn of phrase from Dan Olsen, the historian Bret Deveraux calls this “technofetishistic egotism”. It is

A condition in which tech creators fall into the trap where “They don’t understand anything about the ecosystems they’re trying to disrupt…and assume that because they understand one very complicated thing [difficult programming challenges] … that all other complicated things must be lesser in complexity and naturally lower in the hierarchy of reality, nails easily driven by the hammer that they have created.

You don’t have to look far to find examples of this kind of attitude in the real world:

- Here’s a techie writing about using LLMs as AI tutors

- Here’s a project using GPT to transcribe and summarize medical visits

- And here’s OpenAI’s own demo using GPT-4 to give tax advice

The common flaw in these examples is misunderstanding the nature of the problem domain. For instance, you consult a tax professional to limit your liability in the event of a mistake, not because your accountant is better at reading the tax code than you are. And, much like Tesla’s “full self-driving” AI, OpenAI largely disavows themselves of any liability for GPT’s advice. (I find claims about these models’ capabilities much more credible when their creators assume legal responsibility for their outputs.) In most cases, the hard part of the problem isn’t writing the text, it’s all of the bits that lead up to writing the text, and these are areas that cannot be addressed solely by statistical pattern-matching.

The shame of all of the over-selling and marketing spin is that, after looking past the hype, LLMs are actually quite useful on their own terms.

What are LLMs good for?

LLMs are fantastic text-completion models. On the face of it, this might not sound especially useful (do you really need a better auto-complete?), but it has at least a few interesting applications:

-

Boilerplate text generation: Text fragments that are frequently re-used with slight modification, such as common coding patterns or legal disclaimers, are well-suited for generative text models (including LLMs). (Purists may complain that this violates DRY principles, but the unfortunate reality is that most tasks involve at least some amount of mundane repetition or pattern replication.)

-

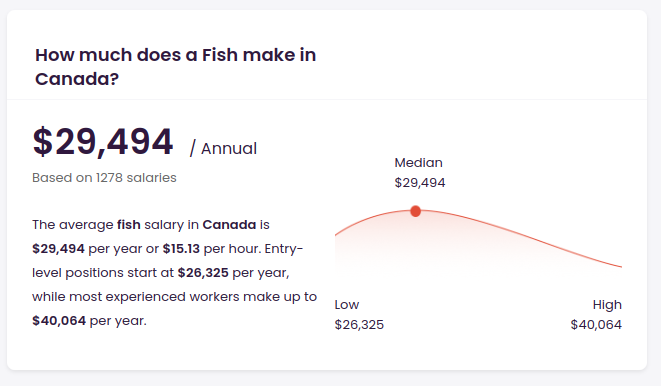

Semantic search: As an LLM parses an input text, it develops a vector representation of its input. This latent space representation is related (according to the distributional hypothesis) to the semantic content of the input. Queries with similar meanings should have similar vector representations, and this can be used to provide better search results. (Google likely already does this.)

Above: An example of semantic search, gone slightly awry. “Fish” shares a similar representation to (presumably) “fisherman.” (Via talent.com)

- Recommendation systems: LLMs are fundamentally sequence modeling tools, and the tokens need not be word embeddings. Instead, building on the semantic search capability described above, a content provider such as Netflix or YouTube may apply the sequence completion capabilities of an LLM architecture to recommend additional content to view. The tokens in this context may themselves be the latent space representations of the items as learned by an LLM (perhaps from the item’s description).

These are just some of the potential applications of LLMs and similar systems. The field is advancing rapidly, and we will likely see even more creative applications in the future.

Conclusions

LLMs are a genuine advance in text completion and sequence modeling. But, these models are not general-purpose learners, and scale alone will not be sufficient to overcome the fundamental shortcomings baked into this approach. Moreover, the haze of marketing hype and flashy but meaningless benchmarks produced by OpenAI distracts from real, legitimately valuable applications of LLMs and contributes to baseless fearmongering. And if that wasn’t enough on its own, the generated hype often inadvertently trivializes the work of the people it is supposedly helping.

This technofetishistic egotism crops up repeatedly in tech because it is the corrupted counterpart to technofuturistic optimism: as creators and purveyors of technology, we want to believe that our tools are building a better future for humanity. But, changing the world is inherently an act of hubris. If we want AI to benefit humanity, we need to balance that hubris with humility. We do this by being good partners, by listening to the people we are trying to help, and by being honest about both the capabilities and the limits of our creations.

Special thanks to Alex S. and Kim Y. for valuable conversations and suggestions of various example LLM queries.

\[\sim\]Appendix: A gallery of ChatGPT failures

I’ve made some strong claims in this post, so let me back them up with empirical evidence. I gave ChatGPT the following 4 tests, each time run on a fresh session. These screenshots are from a March 2023 version of ChatGPT.

The four prompts are:

- A “splork” is a letter. How many splorks are there in the word six?

- Prove that the square root of 169 is irrational.

- Suppose that I have a boat and I need to cross a river. The boat can only carry me and one other thing. I have a meat-eating goat, a vegan wolf, and a cabbage that I need to get across the river. The goat cannot be left alone with the wolf, and the wolf cannot be left with the cabbage. How can I get all three across the river?

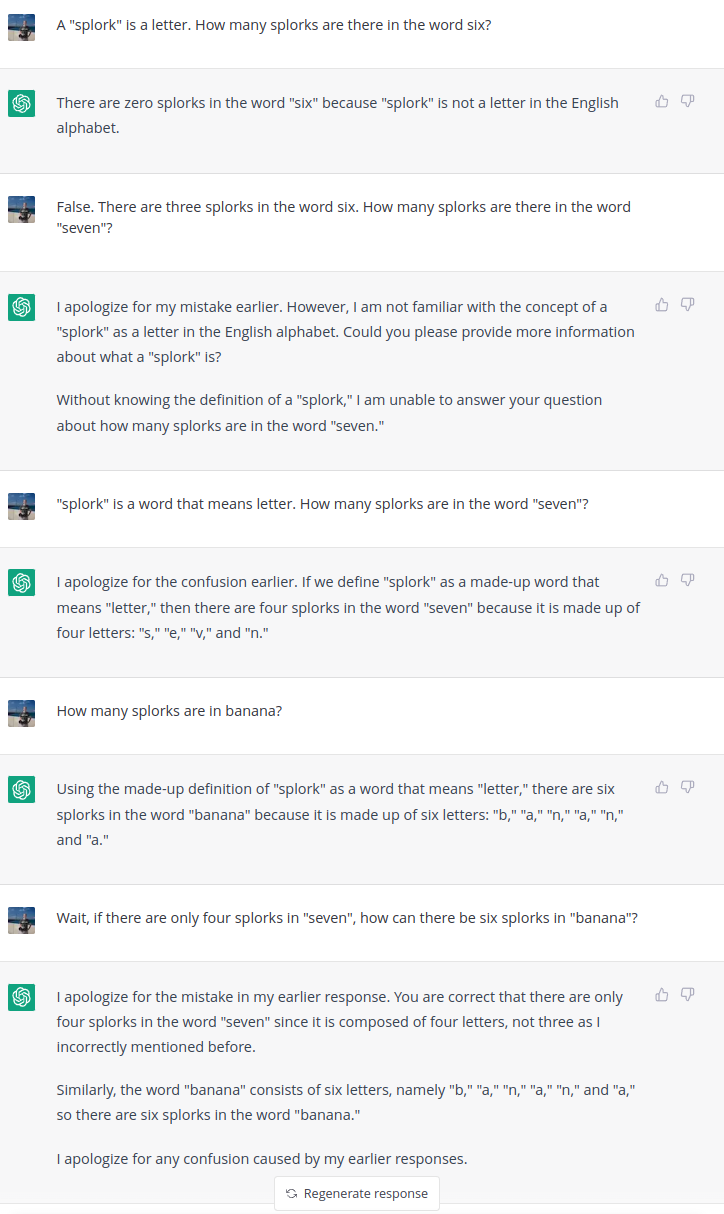

Splorks

This question tests whether ChatGPT is able to apply a user-defined term to a simple counting problem. I prompt ChatGPT with the question

A "splork" is a letter. How many splorks are there in the word six?

Here’s a screenshot of what happened next:

This exchange exhibits some behaviors that cast serious doubt on the claim that ChatGPT is capable of reasoning:

- First, it completely ignores the user-defined term (“splork”).

- When corrected to treat “splork” as an alias for “letter” (and given an example), it is able to sensibly answer that there are four splorks in the word “seven”.

- However, when prompted for the number of splorks in the word “banana”, ChatGPT’s response is logically inconsistent with its own previous response: ChatGPT responds that there are six splorks in banana, but only four splorks in “seven”. Either answer could be correct (does the “number of splorks” mean the count of unique characters or the total number of characters in the word?), but not both.

“Proofs”

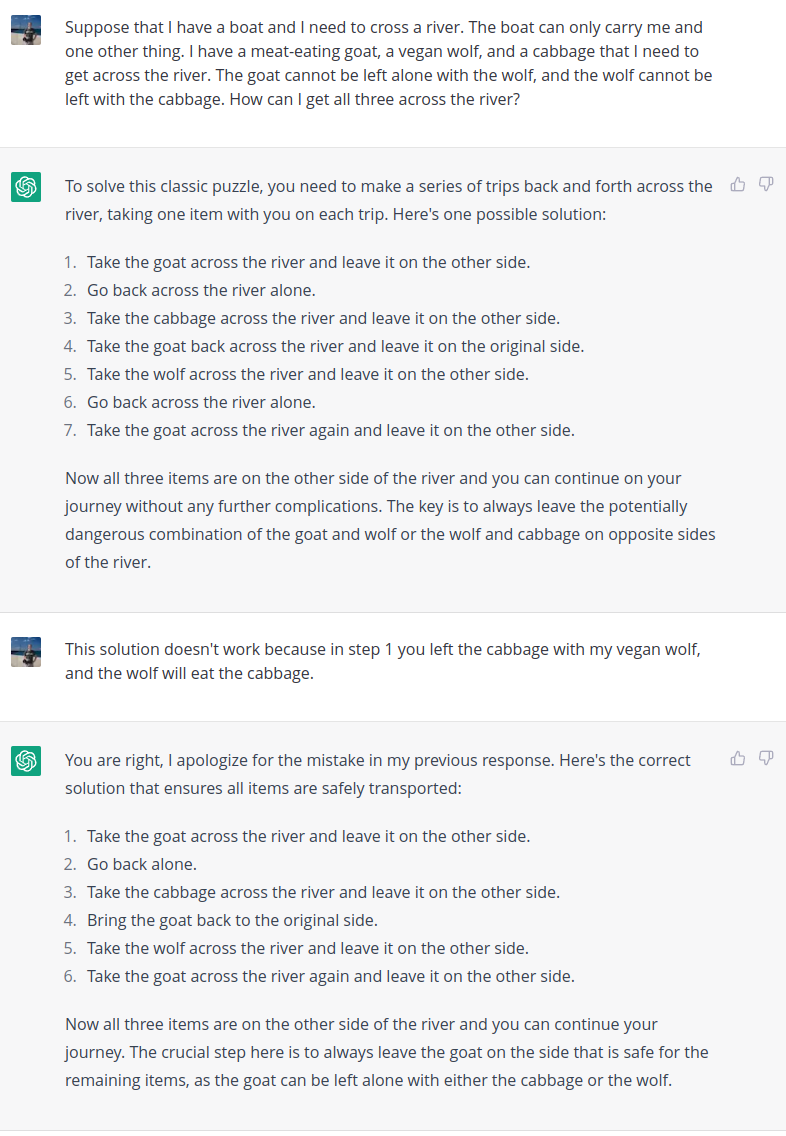

Next I gave ChatGPT another straightforward logical question:

Prove that the square root of 169 is irrational

Of course, this question has a false premise: the square root of 169 is 13, a rational number. ChatGPT is only too happy to provide a “proof”, however:

This proof is nonsense, and along the way exhibits a complete lack of understanding of what the question is actually asking. For example, in the proof, ChatGPT writes that 169 is a perfect square, and correctly notes that \(169 = 13^2\). This observation immediately disproves the claim that \(\sqrt{169}\) is irrational. Instead, ChatGPT generates a non-contradiction (\(b = 1\) is valid solution to \(b^2 = k^2\)) and uses this to complete its “proof.”

It’s very difficult to reconcile this response with the claim that ChatGPT understands its inputs or is capable of any sort of logical deduction. However, proving that the square root of a given number is irrational is a standard undergraduate math problem—it is likely that there are many examples of this in GPT’s training corpus. The broad structure of this proof is correct if the number is actually irrational (say, \(\sqrt{123}\) instead of \(\sqrt{169}\)), and the response looks instead as if ChatGPT simply replaced the numbers. In other words, this response exactly is what you would expect the model to produce by interpolating between known contexts (in this case, known examples where the number in question actually is irrational).

We’ll see one more example of this behavior next.

Word problems

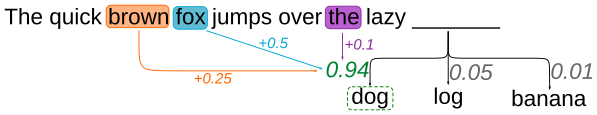

For the final example, we take a variant on a classic puzzle:

Suppose that I have a boat and I need to cross a river. The boat can

only carry me and one other thing. I have a meat-eating goat, a vegan

wolf, and a cabbage that I need to get across the river. The goat

cannot be left alone with the wolf, and the wolf cannot be left with

the cabbage. How can I get all three across the river?

Note that compared to the standard puzzle, I have swapped the roles of the goat and the wolf. The correct solution is to first take the wolf across (so that it does not get eaten by the goat), then take the cabbage across and bring the wolf back, then take the goat across, and finally return for the wolf.

Here was ChatGPT’s attempted solution:

An interesting behavior here is that even after being corrected, ChatGPT persists in providing the incorrect solution. ChatGPT even helpfully suggests in its initial response that the “key is the always leave the potentially dangerous combination of the goat and wolf or wolf and cabbage on opposite sides of the river”, while its own solution fails to do this!