Whatly regards her speechitating?

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal has an excellent comic in which a high school English teacher invents a fake thesaurus as punishment for her students. I like this idea a lot! However, there are a lot of words in a thesaurus, and I’m a busy (okay, lazy) guy. Instead, I decided to make the computer do the work for me. This post is the story of how I trained a model to generate fake English.

Context

Here’s the original comic in question (source)

For this post, I’ll focus on the process of inventing fake words—inventing fake definitions for those words is a bit harder!

Setting up the model

There are a few different approaches to generating random text. One of the simplest and oldest is via a Markov chain, and the deep learning approach I’ll use here can be thought of as a generalization of this technique.

A Markov model consists of a collection of states $s_i$, together with transition probabilities

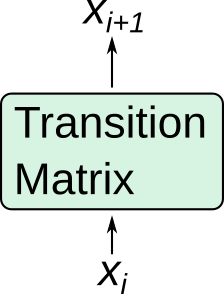

\[p_{ij} := P(s_{t+1} = s_{j} | s_{t} = s_{i}).\]It is natural to represent each state with a one-hot encoded vector, and in this representation the $p_{ij}$ form a matrix called the Markov model’s transition matrix. This transition matrix essentially defines the model.

Here’s a very simple diagram of how this looks:

(This diagram is trivial, but the more complicated model we’ll build below is a natural generalization of it!)

“Training” a Markov model involves figuring out what the transition probabilities are. One simple way to do this is to pick the relative frequencies from the data, e.g. if state $s_j$ follows state $s_i$ 30% of the time, then $p_{ij} = 0.3$. A more sophisticated iterative approach is to pick a random initial transition matrix, and then attempt to maximize the mean log probability of each sequence in the data set. (This second approach is almost certainly overkill if you have a finite number of states, but possibly generalizes better.)

What are states, exactly?

For our word generation model, the states are just characters (“a”, “b”, etc). In a fancier model, you might choose to use multiple characters as a state (“th”, for example), or combinations of single-character and multiple-character states. The technical term for this is a “token”, and the process of breaking up a collection of text into sequences of subsets is called “tokenization”.

In my model, the tokens come in three forms:

- Single letters (like “a”);

- Apostrophes and other punctuation marks that sometimes show up in my list of English words; and

- Special start and stop tokens.

The start and stop tokens don’t represent text at all—instead, they indicate the beginning and end of a sequence, and are how our generative model will tell us when a word has ended.

Data ingress and tokenization

I have a text file of about 77,000 newline-delimited English words on my machine, which I collected from the system’s spellchecker.

(If you’re on a Linux machine, you can probably find it in /usr/share/dict/words or /usr/dict/words).

It only takes a couple of lines to do the tokenization on this file (in Julia):

words = []

open("/path/to/words.txt") do f

for line in eachline(f)

push!(words, vcat(["<SOS>"], split(line, ""), ["<EOS>"]))

end

end

Here, I’m using "<SOS>" (“start of sequence”) as my start token and "<EOS>" (“end of sequence”) as my stop token.

The generative model I’ll implement here is similar to the Markov model described above: its input is a vector representing the current state in the sequence, and its output is a vector of probabilities, representing the likelihood of each state following the input state.

Once we’ve ingested all of the words, we need to generate a “vocabulary” (i.e., a list of all possible states). The easy way to do this is just to keep track of all the unique characters we find.

vocab = Set([])

for w in words

push!(vocab, w...)

end

vocab_list = [v for v in vocab]

A Set will automatically discard any repeated characters, but it’s also more convenient to work with an ordered list (vocab_list).

In my dataset, the vocabulary ends up including 41 tokens (a through z, plus some punctuation characters and our <SOS> and <EOS> tokens).

The model

Next, let’s set up our model. The Markov-style model described above might be a good starting point, but modern language models are quite a bit more complicated. Here, I’m going to use a model based on a type of recurrent network architecture called long short-term memory (LSTM). Note that it’s probably more accurate to call this an “early modern” language model—the state of the art (at least in 2021) has moved on to attention and transformer-based architectures.

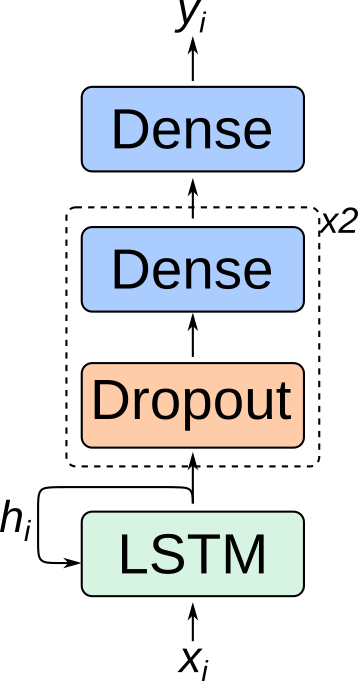

Like all recurrent networks, an LSTM can be thought of as a function that takes in two inputs (the previous hidden state, and the observation) and produces the next hidden state:

\[LSTM(h_{i-1}, x_{i}) = h_{i}\](In fact, in contrast to a vanilla RNN, an LSTM’s hidden state actually consists of two components. But that won’t matter for us.) Generally, the hidden state $h_{i}$ isn’t all that useful on its own, so to make predictions with an LSTM you stack a couple of dense layers to map the hidden state to the target. And this is exactly how our model will look:

Julia’s Flux.jl library makes setting up this kind of model (and deploying it to a GPU) super easy:

model = Chain(

LSTM(41, 128),

Dropout(0.2),

Dense(128, 128, relu),

Dropout(0.2),

Dense(128, 128, relu),

Dropout(0.2),

Dense(128, 41)

) |> gpu

I’ve included Dropout layers for regularization (to reduce the chances of memorizing the training data).

The LSTM layer takes in a 41-dimensional vector (the one-hot-encoded representation of a token from our vocabulary) and produces a 128-dimensional hidden state.

The first dropout layer sets 20% of the neurons to zero at random during training.

Then, a dense layer with a rectified linear activation maps the 128-dimensional hidden state to another 128-dimensional intermediate representation.

I repeat this process once more, and then map the resulting 128-dimensional latent vector to a 41-dimensional vector of transition probabilities.

These transition probabilities represent the chance of that particular state following the observed input state, just like in our simple Markov model.

Some innards

To get this whole model working and useable, we need to define a couple of helper functions. First, the one-liners:

onehot(x) = Flux.onehotbatch(x, vocab_list)

weighted_sample(probs) = sample(1:41, ProbabilityWeights(softmax(probs)))

wordify(batch) = vocab_list[mapslices(weighted_sample, batch, dims=1)]

stringify(words) = join(words[2:end-1], "")

These functions onehot-encoded our tokens, randomly pick a token index based on the input probabilities, turn an array of token probabilities into a “word” (an array of tokens), and turn an array of characters into an actual word (minus the start/stop tokens), respectively.

With these ingredients and a model, we can start generating some words:

function generate(model; max_length=26)

text = ["<SOS>"]

Flux.reset!(model)

Flux.testmode!(model)

while size(text, 1) < max_length

next_word = model(onehot(text[end:end]))

push!(text, wordify(next_word)...)

if text[end] == "<EOS>"

break

end

end

return text

end

If you wanted to be clever, you might add some kind of “temperature” parameter to the weighted_sample function to interpolate between a purely random choice and always choosing the most probable token.

This function takes our language model, feeds in a “start of sequence” token, and then generates characters until either an “end of sequence” token is produced, or the generated word exceeds 25 characters.

We can feed the output of this (an array of tokens) into the stringify function to produce actual words.

So, for example, to generate 5000 words, you might do this:

open("fake_words.txt", "w") do io

for _ in 1:5000

write(io, stringify(generate(model)))

write(io, "\n")

end

end

Training the model

Now that we’ve designed this model, we want it to produce something approximating English language. There are a few competing philosophies about the optimal way to train sequence-based models (“teacher forcing”, batch sizes, etc), but my inclination is to generally do it in the simplest way possible. The optimization criterion I’m going to use is the per-token cross entropy (just like a typical multinomial labeling problem). Because words can be of different lengths (who knew???), I am going to train one word at a time, rather than on a batch of sequences. And, I am going to apply the optimization criterion to each pair of (generated, true) tokens, accumulate gradients, and do the update at the end of the sequence. I’ll do this until the model has probably seen every word in the dataset.

Here is exactly that, in code:

optim = Flux.Optimise.ADAM() # optimizer

pars = Flux.params(model) # grab model parameters

# per-token criterion

criterion = Flux.Losses.logitcrossentropy

for _ in 1:n_words

# pick a random word

idx = sample(1:size(words, 1))

# make sure the dropout layers are active

Flux.trainmode!(model)

# reset the hidden state

Flux.reset!(model)

# construct the input sequence from that word

w = convert(Matrix{Float32}, onehot(words[idx])) |> gpu

# the input is tokens 1,...,n-1

# the target is tokens 2,...,n

x = w[:,1:end-1]

y = w[:,2:end]

# we accumulate gradients at each step

gs = []

for i in 1:size(x, 2)

# calculate gradients

grads = gradient(pars) do

criterion(model(x[:,i:i]), y[:,i:i])

end

push!(gs, grads) # save them to our array

end

# average out the gradients

grads = gs[1]

for g in gs[2:end]

grads = grads .+ g

end

grads = grads ./ size(gs, 1)

# update model parameters using ADAM

Flux.update!(optim, pars, grads)

end

Generated words

At the end of it all, this whole operation works—or at least, creates a model that can generate fake words without crashing. Interestingly, after generating 5000 fake words, I found very few true English words present. Perhaps this is a reflection of how sparse English actually is in the space of 26-token-or-less words with a 41-token vocabulary. Anyway, here are some examples:

immenecipading

grampily

bluloonus

grentled

mecinational

repectellation

assobled

gabblers

confaction

cheemous

sullebagations

decusionate

wanfilate

nibbient

overnoration

delatious

swoured

hagrabelia

scurbotchinate

Thanks for reading! I hope you found this post to a nibbient confaction of assobled gabblers, and that it improved your repectellation for this cheemous subject. With luck, I didn’t scurbotchinate anything important and there aren’t too many delatious sullebagations in the code samples!

```